Mother and Child Family Residential Services in Utah

The family structure of African Americans has long been a matter of national public policy interest.[2] A 1965 study by Daniel Patrick Moynihan, known every bit The Moynihan Written report, examined the link between black poverty and family structure.[2] It hypothesized that the destruction of the black nuclear family structure would hinder farther progress toward economic and political equality.[2]

When Moynihan wrote in 1965 on the coming destruction of the black family, the out-of-spousal relationship birth rate was 25% amidst black people.[3] In 1991, 68% of black children were born outside of marriage (where 'marriage' is divers with a government-issued license).[four] In 2011, 72% of blackness babies were born to single mothers,[5] [6] while the 2018 National Vital Statistics Report provides a figure of 69.4 percent for this condition.[7]

Amid all newlyweds, 18.0% of black Americans in 2015 married non-blackness spouses.[8] 24% of all blackness male person newlyweds in 2015 married exterior their race, compared with 12% of black female newlyweds.[8] 5.v% of blackness males married white women in 1990.[9]

History [edit]

An African American family, photographed between 1918-22. Courtesy of the DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist Academy.

According to data extracted from 1910 U.S. Census manuscripts, compared to white women, black women were more probable to become teenage mothers, stay unmarried and have matrimony instability, and were thus much more likely to live in female person-headed single-parent homes.[10] [eleven] This pattern has been known as black matriarchy because of the observance of many households headed by women.[11]

The breakdown of the black family unit was offset brought to national attending in 1965 past sociologist and later Democratic Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, in the groundbreaking Moynihan Study (also known equally "The Negro Family: The Case For National Action").[12] Moynihan's written report fabricated the argument that the relative absence of nuclear families (those having both a married father and mother nowadays) in black America would greatly hinder further black socio-economic progress.[12]

The current most widespread African-American family construction consisting of a single parent has historical roots dating back to 1880.[13] A study of 1880 family structures in Philadelphia, showed that iii-quarters of black families were nuclear families, equanimous of two parents and children.[14] Data from U.S. Census reports reveal that between 1880 and 1960, married households consisting of two-parent homes were the nearly widespread form of African-American family unit structures.[xiii] Although the most popular, married households decreased over this time period. Unmarried-parent homes, on the other manus, remained relatively stable until 1960; when they rose dramatically.[13]

In the Harlem neighborhood of New York City in 1925, 85 percent of kin-related black households had 2 parents.[15] When Moynihan warned in his 1965 written report on the coming devastation of the black family, even so, the out-of-matrimony birthrate had increased to 25% among the blackness population.[12] This effigy connected to rise over time and in 1991, 68% of black children were born exterior of marriage.[16] U.Southward. Census data from 2010 reveal that more African-American families consisted of single mothers than married households with both parents.[17] In 2011, it was reported that 72% of black babies were born to unmarried mothers.[eleven] Equally of 2015, at 77.iii percent, blackness Americans have the highest rate of non-marital births among native Americans.[18]

In 2016 29% of African Americans were married, while 48% of all Americans were. Too, 50% of African Americans accept never been married in contrast to 33% of all Americans. In 2016 simply under half (48%) of black women had never been married which is an increment from 44% in 2008 and 42.7% in 2005. 52% of black men had never been married. Also, fifteen% pct of blackness men were married to non-blackness women which is up from eleven% in 2010. Blackness women were the least probable to marry not-black men at only vii% in 2017.[19]

The African-American family structure has been divided into a twelve-function typology that is used to show the differences in the family structure based on "gender, marital condition, and the presence or absence of children, other relatives or non-relatives."[20] These family sub-structures are divided up into 3 major structures: nuclear families, extended families, and augmented families.

African-American families at a glance [edit]

African-American nuclear families [edit]

Andrew Billingsley'due south research on the African-American nuclear family is organized into four groups: Incipient Nuclear, Simple Nuclear, Segmented Nuclear I, and Segmented Nuclear II.[xx] In 1992 Paul Glick supplied statistics showing the African-American nuclear family structure consisted of fourscore% of total African-American families in comparison to 90% of all US families.[21] According to Billingsley, the African-American incipient nuclear family unit structure is divers every bit a married couple with no children.[20]

In 1992 47% of African-American families had an incipient nuclear family in comparing to 54% of all U.s. incipient nuclear families.[22] The African-American uncomplicated nuclear family structure has been divers as a married couple with children.[20] This is the traditional norm for the composition of African-American families.[23] In 1992 25% of African-American families were simple nuclear families in comparison to 36% of all The states families.[22] About 67 per centum of black children are born into a single parent household.[24]

The African-American segmented nuclear I (unmarried female parent and children) and 2 (unmarried father and children) family structures are defined every bit a parent–child relationship.[20] In 1992, 94% of African-American segmented nuclear families were composed of an unmarried mother and children.[22] Glick's enquiry found that single parent families are twice as prevalent in African-American families every bit they are in other races, and this gap continues to widen.[21]

African-American extended families [edit]

Billingsley's inquiry connected with the African-American extended family unit structure, which is composed of primary members plus other relatives.[20] Extended families have the same sub-structures as nuclear families, incipient, simple, segmented I, and segmented Ii, with the addition of grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins and boosted family members. Billingsley's inquiry constitute that the extended family structure is predominantly in the segmented I sub-structured families.[xx]

In 1992 47% of all African-American extended families were segmented extended family structures, compared to 12% of all other races combined.[25] Billingsley'south research shows that in the African-American family the extended relative is ofttimes the grandparents.[26]

African-American augmented families [edit]

Billingsley'due south enquiry revealed another type of African-American family unit, called the augmented family unit construction, which is a family equanimous of the primary members, plus nonrelatives.[xx] Billingsley's instance written report found that this family structure accounted for 8% of black families in 1990.[27] This family construction is different from the traditional norm family discussed before, it combines the nuclear and extended family unit units with nonrelatives. This structure also has the incipient, elementary, segmented I, and segmented Ii sub-structures.[20]

Not-family households [edit]

Billingsley introduced a new family structure that branches from the augmented family structure.[27] The African-American population is starting to run into a new structure known every bit a non-family household. This non-family unit household contains no relatives.[28] Co-ordinate to Glick in 1992, 37% of all households in the Us were a nonfamily household, with more than half of this pct beingness African-Americans.[29]

African-American interracial marriages [edit]

Among all newlyweds, 18.0% of Blackness Americans in 2015 married someone whose race or ethnicity was different from their own.[viii] 24% of all Black male person newlyweds in 2015 married outside their race, compared with 12% of Blackness female newlyweds.[8]

In the Usa at that place has been a historical disparity between Black female and Back male exogamy ratios. There were 354,000 White female person/Black male and 196,000 Blackness female/White male person marriages in March 2009, representing a ratio of 181:100.[xxx]

This traditional disparity has seen a rapid reject over the last ii decades, contrasted with its peak in 1981 when the ratio was still 371:100.[31] In 2007, 4.6% of all married Black people in the United States were midweek to a White partner, and 0.four% of all Whites were married to a Black partner.[32]

The overall charge per unit of African-Americans marrying non-Blackness spouses has more than than tripled between 1980 and 2015, from five% to eighteen%.[eight]

African-American family members at a glance [edit]

E. Franklin Frazier has described the current African-American family construction every bit having two models, one in which the father is viewed every bit a patriarch and the sole breadwinner, and ane where the female parent takes on a matriarchal role in the identify of a fragmented household.[33] In defining family, James Stewart describes it as "an institution that interacts with other institutions forming a social network."[23]

Stewart's research concludes that the African-American family unit has traditionally used this definition to structure institutions that upholds values tied to other black institutions resulting in unique societal standards that bargain with "economics, politics, pedagogy, health, welfare, law, culture, faith, and the media."[34] Ruggles argues that the mod blackness U.Southward. family has seen a alter in this tradition and is now viewed as predominantly single parent, specifically black matriarchy.[13]

Father representative [edit]

In 1997, McAdoo stated that African-American families are "frequently regarded as poor, fatherless, dependent of governmental assistance, and involved in producing a multitude of children outside of wedlock."[35] Thomas, Krampe and Newton show that in 2005 39% of African-American children did not alive with their biological father and 28% of African-American children did non live with any father representative, compared to xv% of white children who were without a father representative.[36] In the African-American civilization, the father representative has historically acted as a office model for two out of every three African-American children.[37]

Thomas, Krampe, and Newton relies on a 2002 survey that shows how the father's lack of presence has resulted in several negative furnishings on children ranging from education operation to teen pregnancy.[38] Whereas the father presence tends to have an opposite effect on children, increasing their chances on having a greater life satisfaction. Thomas, Krampe, and Newton's enquiry shows that 32% of African-American fathers rarely to never visit their children, compared to 11% of white fathers.[36]

In 2001, Hamer showed that many[ vague ] African-American youth did not know how to approach their father when in his presence.[39] This survey also concluded that the not resident fathers who did visit their child said that their role consisted of primarily spending fourth dimension with their children, providing subject area and beingness a role model.[40] John McAdoo besides noted that the residential begetter function consists of being the provider and decision maker for the household.[41] This concept of the male parent'south role resembles the theory of hegemonic masculinity. Quaylan Allan suggests that the continuous comparison of white hegemonic masculinity to black manhood, tin can also add together a negative upshot on the presence of the father in the African-American family structure[42]

Female parent representative [edit]

Melvin Wilson suggests that in the African-American family unit structure a female parent'south role is adamant by her relationship condition, is she a unmarried mother or a married mother?[43] According to Wilson, in most African-American married families a mother'due south roles is dominated by her household responsibilities.[44] Wilson inquiry states that African American married families, in contrast to White families, practice not accept gender specific roles for household services.[45] The mother and wife is responsible for all household services around the house.[44]

According to Wilson, the married female parent'due south tasks around the house is described equally a full-time job. This full-time task of household responsibilities is often the 2nd job that an African-American woman takes on.[45] The first job is her regular 8 hr piece of work day that she spends exterior of the home. Wilson too notes that this responsibleness that the mother has in the married family determines the life satisfaction of the family as a whole.[45]

Melvin Wilson states that the single mother role in the African-American family is played by 94% of African-American single parents.[46] According to Brown, unmarried parent motherhood in the African-American culture is becoming more than a "proactive" choice.[47] Melvin Wilson's inquiry shows 62% of unmarried African-American women said this choice is in response to divorce, adoption, or merely not marriage compared to 33% of single white women.[48] In this position African-American single mothers see themselves playing the office of the mother and the father.[47]

Though the role of a unmarried mother is similar to the function of a married mother, to accept care of household responsibilities and work a total-time task, the unmarried mothers' responsibility is greater since she does not have a second political party income that a partner would provide for her family members. According to Brown, this lack of a 2nd party income has resulted in the majority of African American children raised in single mother households having a poor upbringing.[49]

Child [edit]

In Margaret Spencer's instance study on children living in southern metropolitan areas, she shows that children can merely grow through enculturation of a particular society.[50] The child'southward evolution is dependent on three areas: kid-rearing practices, individual heredity, and experienced cultural patterns. Spencer'southward research also concludes that African-American children have become subject area to inconsistencies in lodge based on their skin color.[51] These inconsistencies continue to place an increased amount of environmental stress on African-American families which result in the failure of about African-American children to achieve their full potential.[52]

Similar to most races, challenges that African-American families experience are usually dependent on the children's age groups.[53] The African-American families experience a slap-up deal of mortality inside the infant and toddler age group. In particular the babe mortality rate is "twice as high for blackness children as for children in the nation as a whole."[53] The bloodshed in this age grouping is accompanied by a significant number of illnesses in the pre- and mail-natal care stages, along with the failure to identify these children into a positive, progressive learning environment once they become toddlers.[54] This foundation has led to African-American children facing teen pregnancy, juvenile detention, and other behavioral issues because they were not given the proper development to successfully confront the world and social inconsistencies they will encounter.[54]

Extended family members [edit]

Jones, Zalot, Foster, Sterrett, and Chester executed a written report examining the childrearing assistance given to young adults and African-American single mothers.[55] The bulk of extended family members, including aunts, uncles, cousins, grandparents, and occasionally non-relatives, are put into this category.[55] : 673 In Jones research she also notes that 97% of single mother'southward ages 28–twoscore admitted that they rely on at least one extended family unit fellow member for assistance in raising their children.[55] : 676

Extended family members have an immense amount of responsibility in the majority of African-American families, especially single parent households. Co-ordinate to Jones, the reason these extended family members are included in having a necessary role in the family is because they play a key role in assuring the health and well-existence of the children.[55] : 673 The extended family members' responsibilities range from child rearing, fiscal assistance, offering a place to live, and meals.[55] : 674

Theories [edit]

Economical theories [edit]

There are several hypotheses – both social and economic – explaining the persistence of the current African-American family unit structure. Some researchers conjecture that the low economic statuses of the newly freed slaves in 1850 led to the current family unit construction for African Americans. These researchers suggest that extreme poverty has increased the destabilization of African American families while others point to high female labor participation, few job opportunities for blackness males, and modest differences between wages for men and women that accept decreased wedlock stability for black families.[13]

Another economic theory dates back to the belatedly 1950s and early '60s, the cosmos of the "Human being-in-the-Firm" rule; this restricted ii parent households from receiving government benefits which fabricated many blackness fathers move out to be able to receive help to support their families. These rules were later abolished when the Supreme Court ruled confronting these exclusions in the case of King vs Smith.[56]

Economical status has proved to not always negatively bear on unmarried-parent homes, however. Rather, in an 1880 census, there was a positive relationship between the number of blackness single-parent homes and per-capita county wealth.[13] Moreover, literate young mothers in the 1880s were less likely to reside in a home with a spouse than illiterate mothers.[13] This suggests that economic factors post-obit slavery alone cannot account for the family styles seen by African Americans since blacks who were illiterate and lived in the worst neighborhoods were the most probable to live in a two-parent domicile.

Traditional African influences [edit]

Other explanations comprise social mechanisms for the specific patterns of the African American family unit structure. Some researchers point to differences in norms regarding the need to live with a spouse and with children for African-Americans. Patterns seen in traditional African cultures are also considered a source for the current trends in single-parent homes. Every bit noted past Antonio McDaniel, the reliance of African-American families on kinship networks for financial, emotional, and social support can be traced back to African cultures, where the accent was on extended families, rather than the nuclear family.[57]

Some researchers have hypothesized that these African traditions were modified by experiences during slavery, resulting in a current African-American family unit structure that relies more on extended kin networks.[57] The author notes that slavery caused a unique situation for African slaves in that it alienated them from both true African and white culture and then that slaves could non place completely with either civilisation. As a result, slaves were culturally adaptive and formed family structures that all-time suit their environment and situation.[57]

Post-1960s expansion of the U.S. welfare state [edit]

The American economists Walter E. Williams and Thomas Sowell argue that the pregnant expansion of federal welfare under the Bully Society programs offset in the 1960s contributed to the devastation of African American families.[58] [59] Sowell has argued: "The black family, which had survived centuries of slavery and discrimination, began chop-chop disintegrating in the liberal welfare state that subsidized unwed pregnancy and changed welfare from an emergency rescue to a way of life."[59]

There are several other factors which may have accelerated refuse of the black family construction such every bit 1) The advancement of technology lessening the need for manual labor to more technical know-how labor; and 2) The women'south rights movement in general opened up employment positions increasing competition, specially from white women, in many non-traditional areas which skilled blacks may have contributed to maintain their family unit structure in the midst of the rise of the toll of living.[60]

Decline of black marriages [edit]

The rate of African American marriage is consistently lower than White Americans, and is declining.[61] These trends are and then pervasive that families who are married are considered a minority family unit structure for blacks.[61] In 1970, 64% of developed African Americans were married. This rate was cutting in half past 2004, when it was 32%.[61] In 2004, 45% of African Americans had never been married compared to just 25% of White Americans.[61]

While research has shown that marriage rates take dropped for African Americans, the birth rate has non. Thus, the number of single-parent homes has risen dramatically for black women. One reason for the low rates of African American marriages is high historic period of first union for many African Americans. For African American women, the marriage rate increases with age compared to White Americans who follow the aforementioned trends only marry at younger ages than African Americans.[61]

One study found that the boilerplate age of marriage for blackness women with a high school caste was 21.viii years compared to 20.8 years for white women.[61] Fewer labor force opportunities and a decline in existent earnings for black males since 1960 are likewise recognized as sources of increasing marital instability.[63] As some researchers argue, these ii trends accept led to a pool of fewer desirable male partners and thus resulted in more than divorces.

One type of marriage that has declined is the shotgun marriage.[64] This drop in rate is documented by the number of out-of-matrimony births that now commonly occur.[64] Between 1965 and 1989, three-quarters of white out-of-marriage births and three-fifths of black out-of-wedlock births could be explained past situations where the parents would take married in the past.[64] This is considering, prior to the 1970s, the norm was such that, should a couple take a pregnancy out of wedlock, marriage was inevitable.[64] Cultural norms take since changed, giving women and men more agency to decide whether or when they should become married.[64]

Rising in divorce rates [edit]

For African Americans who practice marry, the rate of divorce is higher than White Americans. While the trend is the same for both African Americans and White Americans, with at least half of marriages for the two groups ending in divorce, the charge per unit of divorce tends to be consistently higher for African Americans.[61] African Americans also tend to spend less time married than White Americans. Overall, African Americans are married at a later historic period, spend less time married and are more probable to be divorced than White Americans.[61]

The pass up and low success rate of black marriages is crucial for study because many African Americans achieve a middle-grade condition through wedlock and the likelihood of children growing up in poverty is tripled for those in single-parent rather than ii-parent homes.[61] Some researchers propose that the reason for the ascent in divorce rates is the increasing acceptability of divorces. The decline in social stigma of divorce has led to a decrease in the number of legal barriers of getting a divorce, thus making it easier for couples to divorce.[63]

Black male incarceration and mortality [edit]

In 2006 an estimated 4.eight% of black non-Hispanic men were in prison or jail, compared to 1.9% of Hispanic men of whatsoever race and 0.7% of White not-Hispanic men. U.South. Bureau of Justice Statistics.[65]

Structural barriers are often listed as the reason for the current trends in the African American family structure, specifically the decline in wedlock rates. Imbalanced sexual activity ratios have been cited as one of these barriers since the tardily nineteenth century, where Census data shows that in 1984, at that place were 99 black males for every 100 black females within the population.[61] 2003 census data shows there are 91 blackness males for every 100 females.[61]

Blackness male person incarceration and higher bloodshed rates are often pointed to for these imbalanced sex ratios. Although black males make up 6% of the population, they make up 50% of those who are incarcerated.[61] This incarceration charge per unit for black males increased by a rate of more than four between the years of 1980 and 2003. The incarceration rate for African American males is iii,045 out of 100,000 compared to 465 per 100,000 White American males.[61] In many areas effectually the country, the risk that black males will be arrested and jailed at least once in their lifetime is extremely high. For Washington, D.C., this probability is between fourscore and 90%.[61]

Because black males are incarcerated at six times the rate of white males, the skewed incarceration rates harm these black males besides as their families and communities. Incarceration can affect former inmates and their future in society long afterward they leave prison. Those that accept been incarcerated lose masculinity, as incarceration can bear on a man'south confirmation of his identity every bit a begetter. After beingness released from prison, efforts to reestablish or sustain connections and be active inside the family are often unsuccessful.[66]

Incarceration tin be damaging to familial ties and can have a negative result on family unit relations and a man's sense of masculinity.[66] In 34 states, those who are on parole or probation are not allowed to vote, and in 12 states a felony confidence means never voting again.[67] A criminal record affects 1'due south ability to secure federal benefits or get a chore, as 1 Northwestern University study constitute that blacks with a criminal record were the to the lowest degree likely to be called dorsum for a job interview in a comparing of black and white applicants.[68]

Incarceration has been associated with a higher risk of illness, increased likelihood of smoking cigarettes, and premature death, impacting these quondam inmates and their ability to exist normalized in society.[67] This further impacts social structure, as studies show that paternal incarceration may contribute to children's behavioral bug and lower performance in school.[69] Too, the female partners of male inmates are more probable to suffer from depression and struggle economically.[67] These effects contribute to the barriers impacting the African American family structure.

The bloodshed rates for African American males are besides typically college than they are for African American females. Between 1980 and 2003, 4,744 to 27,141 more African American males died annually than African American females.[61] This college incarceration rate and mortality charge per unit helps to explain[ original research? ] the depression union rates for many African American females who cannot discover black partners.

Implications [edit]

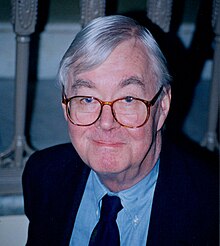

New York'due south tardily Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, photographed in 1998.

The Moynihan Study, written by Assistant Secretary of Labor, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, initiated the debate on whether the African-American family construction leads to negative outcomes, such as poverty, teenage pregnancy and gaps in teaching or whether the reverse is true and the African American family structure is a result of institutional discrimination, poverty and other segregation.[lxx] Regardless of the causality, researchers take constitute a consistent relationship betwixt the current African American family construction and poverty, didactics, and pregnancy.[71] According to C. Eric Lincoln, the Negro family'southward "enduring sickness" is the absent father from the African-American family unit structure.[72]

C. Eric Lincoln as well suggests that the implied American idea that poverty, teen pregnancy, and poor education functioning has been the struggle for the African-American community is due to the absent African-American begetter. According to the Moynihan Report, the failure of a male dominated subculture, which only exist in the African-American civilisation, and reliance on the matriarchal control has been greatly present in the African-American family structure for the past three centuries.[73] This absenteeism of the father, or "mistreatment", has resulted in the African-American crime rate being college than the National average, African-American drug addiction beingness higher than whites, and rates of illegitimacy existence at least 25% or college than whites.[73] A family needs the presence of both parents for the youth to "larn the values and expectations of society."[72]

Poverty [edit]

Black single-parent homes headed by women still demonstrate how relevant the feminization of poverty is. Black women often work in low-paying and female-dominated occupations.[74] [ needs update ] Blackness women likewise make up a large percentage of poverty-afflicted people.[74] Additionally, the racialization of poverty in combination with its feminization creates further hindrances for youth growing up black, in unmarried-parent homes, and in poverty.[74] For married couple families in 2007, there was a 5.8% poverty rate.[75]

This number, still, varied when considering race so that five.4% of all white people,[76] nine.seven% of black people,[77] and 14.ix% of all Hispanic people lived in poverty.[78] These numbers increased for single-parent homes, with 26.vi% of all single-parent families living in poverty,[75] 22.5% of all white unmarried-parent people,[76] 44.0% of all single-parent blackness people,[77] and 33.4% of all unmarried-parent Hispanic people[78] living in poverty.

While majority opinion tends to eye on the increase in poverty as a issue of single-parent homes, enquiry has shown that this is non always the case. In one written report examining the effects of single-parent homes on parental stress and practices, the researchers found that family construction and marital status were non as big a factor every bit poverty and the experiences the mothers had while growing up.[79] Furthermore, the authors found niggling parental dysfunction in parenting styles and efficacy for single-mothers, suggesting that ii-parent homes are non always the only type of successful family structures.[79] The authors propose that focus should likewise be placed on the poverty that African Americans face as a whole, rather than just those who live in unmarried-parent homes and those who are of the typical African American family structure.[79]

Educational operation [edit]

In that location is consensus in the literature near the negative consequences of growing up in single-parent homes on educational attainment and success.[71] Children growing up in single-parent homes are more than likely to non stop schoolhouse and generally obtain fewer years of schooling than those in two-parent homes.[71] Specifically, boys growing up in homes with only their mothers are more likely to receive poorer grades and display behavioral problems.[71]

For blackness high schoolhouse students, the African American family structure also affects their educational goals and expectations.[71] Studies on the topic accept indicated that children growing up in single-parent homes face disturbances in young babyhood, boyhood and young machismo likewise.[71] Although these effects are sometimes minimal and contradictory, it is generally agreed that the family structure a child grows upward in is of import for their success in the educational sphere.[71] This is especially important for African American children who take a 50% chance of existence born outside of marriages and growing upward in a abode with a single-parent.[79]

Some arguments for the reasoning behind this drib in attainment for single-parent homes point to the socioeconomic problems that arise from mother-headed homes. Particularly relevant for families centered on black matriarchy, one theory posits that the reason children of female-headed households do worse in instruction is considering of the economic insecurity that results because of single maternity.[71] Single parent mothers often have lower incomes and thus may be removed from the home and forced to work more than hours, and are sometimes forced to move into poorer neighborhoods with fewer educational resource.[71]

Other theories point to the importance of male office models and fathers in item, for the development of children emotionally and cognitively, peculiarly boys.[71] Even for fathers who may not be in the home, studies have shown that time spent with fathers has a positive relationship with psychological well-being including less low and feet. Additionally, emotional support from fathers is related to fewer delinquency issues and lower drug and marijuana use.[eighty]

Teen pregnancy [edit]

Teenage and unplanned pregnancies pose threats for those who are affected by them with these unplanned pregnancies leading to greater divorce rates for young individuals who marry after having a child. In one study, lx% of the young married parents had separated within the first five years of marriage.[81] Additionally, every bit reported in ane article, unplanned pregnancies are often cited every bit a reason for young parents dropping out, resulting in greater economical burdens and instabilities for these teenage parents after on.[81]

Some other report institute that paternal attitudes towards sexuality and sexual expression at a young historic period were more probable to determine sexual behaviors by teens regardless of maternal opinions on the matter.[81] For these youths, the opinions of the father affected their behaviors in positive means, regardless of whether the parent lived in or out of the home and the age of the student.[81] Some other report looking at how mother–daughter relationships affect teenage pregnancy found that negative parental relationships led to teenage daughters dating afterwards, getting pregnant earlier, and having more than sexual activity partners.[82]

Teens who lived in a married family unit have been shown to take a lower hazard for teenage pregnancy.[83] Teenage girls in unmarried-parent families were six times more likely to become meaning and 2.8 times more than likely to engage in sex at an earlier historic period than girls in married family homes.[84]

Criticism and back up [edit]

Cosby and Poussaint'south criticism of the single-parent family unit [edit]

Nib Cosby has criticized the current state of unmarried-parenting dominating black family structure. In a voice communication to the NAACP in 2004, Cosby said, "In the neighborhood that virtually of usa grew upwards in, parenting is not going on. You take the pile-upwards of these sweet cute things built-in by nature—raised by no one."[85]

In Cosby's 2007 book Come up On People: On the Path from Victims to Victors, co-authored with psychiatrist Alvin Poussaint, Cosby and Poussaint write that "A house without a father is a challenge," and that "A neighborhood without fathers is a ending."[85] Cosby and Poussaint write that mothers "accept difficulty showing a son how to be a human," and that this presents a problem when there are no father figures effectually to show boys how to channel their natural aggressiveness in constructive ways.[85] Cosby and Poussaint also write, "We wonder if much of these kids' rage was built-in when their fathers abandoned them."[85]

Cosby and Poussaint country that verbal and emotional corruption of the children is prominent in the parenting style of some blackness unmarried mothers, with serious developmental consequences for the children.[85] "Words like 'Yous're stupid,' 'You lot're an idiot,' 'I'chiliad lamentable you were born,' or 'You'll never amount to annihilation' tin can stick a dagger in a child's centre."[85] "Single mothers angry with men, whether their current boyfriends or their children's fathers, regularly transfer their rage to their sons, since they're afraid to have it out on the adult males"[85] Cosby and Poussaint write that this formative parenting surround in the black single parent family leads to a "wounded acrimony—of children toward parents, women toward men, men toward their mothers and women in general".[85]

Policy proposals [edit]

Authors Angela Hattery and Earl Smith have proffered solutions to addressing the high rate of black children being built-in out of wedlock.[86] : 285–315 Three of Hattery and Smith's solutions focus on parental back up for children, equal admission to education, and alternatives to incarceration for nonviolent offenders. According to Hattery and Smith, African-American families are inside a system that is "pitted" against them and at that place are some institutional solutions and private solutions that America and its citizens can do to reduce implications associated with the African-American family construction.[86] : 315

Parental back up for children [edit]

According to Hattery and Smith, around 50% of African-American children are poor because they are dependent on a single mother.[86] : 305 In states like Wisconsin, for a child to be the recipient of welfare or receive the "helpmate fare", their parents must exist married.[86] : 306 Hattery acknowledges one truth most this constabulary, which is that it recognizes that a child is "entitled" to the financial and emotional support of both parents. 1 of Hattery and Smith's solutions is constitute effectually the idea that an African-American child is entitled to the financial and emotional support of both parents. The government does require the noncustodial parents to pay a percentage to their child every month, just co-ordinate to Hattery the only way this will help eliminate child poverty is if these policies are actively enforced.[86] : 306

Educational activity equality [edit]

For the by 400 years of America's life many African-Americans have been denied the proper educational activity needed to provide for the traditional American family construction.[86] : 308 Hattery suggests that the schools and education resources available to most African-Americans are under-equipped and unable provide their students with the noesis needed to be college prepare.[86] : 174 In 2005 The Manhattan Constitute for Policy Research written report showed that even though integration has been a push more recently, over the past fifteen years there has been a thirteen% pass up in integration in public schools.[86] : 174

These same reports besides show that in 2002, 56% of African-American students graduated from high school with a diploma, while 78% of whites students graduated. If students exercise non feel they are learning, they will non continue to get to schoolhouse. This conclusion is made from the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research report that stated just 23% of African-American students who graduated from public high school felt college-ready.[86] : 174 Hatterly suggests that the government invest into the African-American family by investing in the African-American children'due south education.[86] : 308 A solution is found in providing the same resources provided to schools that are predominantly white. Co-ordinate to Hatterly, through instruction equality the African-American family structure tin can increase opportunities to prosper with equality in employment, wages, and health insurance.[86] : 308

Alternatives to incarceration [edit]

According to Hattery and Smith 25–33% of African-American men are spending fourth dimension in jail or prison and co-ordinate to Thomas, Krampe, and Newton 28% of African-American children practice not alive with any father representative.[36] [86] : 310 Co-ordinate to Hatterly, the government can end this state of affairs that many African-American children feel due to the absenteeism of their begetter.[86] : 285–315 Hatterly suggests probation or treatment (for booze or drugs) as alternatives to incarceration. Incarceration not merely continues the negative supposition of the African-American family structure, just perpetuates poverty, unmarried parenthood, and the separation of family units.[86] : 310

See besides [edit]

Publications:

- Is Wedlock for White People?: How the African American Union Decline Affects Everyone

Full general:

- African American culture

- Family construction in the United States

- Feminization of poverty

- African Americans and birth control

- Blackness genocide

References [edit]

- ^ *Grove, Robert D.; Hetzel, Alice Chiliad. (1968). Vital Statistics Rates in the The states 1940-1960 (PDF) (Report). Public Health Service Publication. Vol. 1677. U.S. Department of Wellness, Pedagogy, and Welfare, U.S. Public Health Service, National Center for Health Statistics. p. 185.

- Ventura, Stephanie J.; Bachrach, Christine A. (October 18, 2000). Nonmarital Childbearing in the United States, 1940-99 (PDF) (Study). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 48. Centers for Disease Command and Prevention, National Centre for Wellness Statistics, National Vital Statistics Organisation. pp. 28–31.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady East.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Menacker, Fay; Park, Melissa Thousand. (February 12, 2002). Births: Terminal Information for 2000 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 50. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Middle for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 46.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Menacker, Fay; Park, Melissa One thousand.; Sutton, Paul D. (December 18, 2002). Births: Final Data for 2001 (PDF) (Written report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 51. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics Organization. p. 47.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Sutton, Paul D.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Menacker, Fay; Munson, Martha 50. (December 17, 2003). Births: Concluding Data for 2002 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 52. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Wellness Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 57.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady East.; Sutton, Paul D.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Menacker, Fay; Munson, Martha L. (September eight, 2005). Births: Final Information for 2003 (PDF) (Study). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 54. Centers for Affliction Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 52.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady Eastward.; Sutton, Paul D.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Menacker, Fay; Kirmeyer, Sharon (September 29, 2006). Births: Final Data for 2004 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 55. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Centre for Wellness Statistics, National Vital Statistics Organization. p. 57.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady Due east.; Sutton, Paul D.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Menacker, Fay; Kirmeyer, Sharon; Munson, Martha L. (December 5, 2007). Births: Final Data for 2005 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 56. Centers for Affliction Control and Prevention, National Centre for Wellness Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 57.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Sutton, Paul D.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Menacker, Fay; Kirmeyer, Sharon; Mathews, T.J. (Jan 7, 2009). Births: Final Information for 2006 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 57. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Eye for Wellness Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 54.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady Due east.; Sutton, Paul D.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Mathews, T.J.; Kirmeyer, Sharon; Osterman, Michelle J.K. (Baronial 9, 2010). Births: Final Data for 2007 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 58. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Eye for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 46.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Sutton, Paul D.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Mathews, T.J.; Osterman, Michelle J.K. (December 8, 2010). Births: Terminal Information for 2008 (PDF) (Study). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 59. Centers for Illness Command and Prevention, National Eye for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics Organization. p. 46.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Osterman, Michelle J.Thou.; Kirmeyer, Sharon; Mathews, T.J.; Wilson, Elizabeth C. (November three, 2011). Births: Final Data for 2009 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. sixty. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Heart for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics Arrangement. p. 46.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Osterman, Michelle J.G.; Wilson, Elizabeth C.; Mathews, T.J. (August 28, 2012). Births: Concluding Data for 2010 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 61. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics Organisation. p. 45.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Osterman, Michelle J.1000.; Mathews, T.J. (June 28, 2013). Births: Final Data for 2011 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 62. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 43.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Osterman, Michelle J.Grand.; Curtin, Sally C. (December xxx, 2013). Births: Final Information for 2012 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 62. Centers for Affliction Control and Prevention, National Eye for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 41.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady Due east.; Osterman, Michelle J.K.; Curtin, Sally C.; Mathews, T.J. (January 15, 2015). Births: Terminal Data for 2013 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 64. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Wellness Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. twoscore.

- Hamilton, Brady E.; Martin, Joyce A.; Osterman, Michelle J.Chiliad.; Curtin, Sally C.; Mathews, T.J. (December 23, 2015). Births: Last Data for 2014 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 64. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. pp. 7 & 41.

- ^ a b c "Moynihan's State of war on Poverty study". Archived from the original on 2017-01-20. Retrieved 2015-07-31 .

- ^ Daniel P. Moynihan, The Negro Family: The Case for National Action, Washington, D.C., Office of Policy Planning and Inquiry, U.S. Department of Labor, 1965.

- ^ National Review, Apr 4, 1994, p. 24.

- ^ "Blacks struggle with 72 per centum unwed mothers rate", Jesse Washington, NBC News, July xi, 2010

- ^ "For blacks, the Pyrrhic Victory of the Obama Era, Jason 50. Riley, The Wall Street Journal, November 4, 2012

- ^ "National Vital Statistics Reports" (PDF). 68 (thirteen). Nov 27, 2019: 9. Retrieved ane January 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Pew Research Intermarriage in the U.S. 50 Years After Loving v. Virginia May 18, 2017

- ^ Wong, Linda Y. (2003). "Why and so only 5.5% of Black Men Ally White Women?". International Economical Review. 44 (3): 803–826. doi:10.1111/1468-2354.T01-1-00090. S2CID 45703289.

- ^ Morgan, S.; Antonio McDaniel; Andrew T. Miller; Samuel H. Preston. (1993). "Racial differences in household and family construction at the turn of the century". American Journal of Sociology. 98 (4): 799–828. doi:10.1086/230090. S2CID 145358763.

- ^ a b c Washington, Jesse (2010-11-06). "Blacks struggle with 72 percentage unwed mothers rate - Boston.com". AP . Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ a b c Daniel P. Moynihan, The Negro Family unit: The Case for National Action, Washington, D.C., Office of Policy Planning and Research, U.S. Department of Labor, 1965.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ruggles, Due south. (1994). The origins of African-American family structure. American Sociological Review, 136–151.

- ^ Hershberg, Theodore (Wintertime 1971–1972). "Free Blacks in Antebellum Philadelphia: A Written report of Ex-Slaves, Freeborn, and Socioeconomic Decline". Journal of Social History. five (2): 190. doi:10.1353/jsh/5.ii.183. JSTOR 3786411.

Information from the Abolitionist and Quaker censuses, the U. S. Demography of 1880 and W. Due east. B. Du Bois' report of the seventh ward in 1896–97 indicate, in each instance, that 2-parent households were characteristic of 78 per centum of blackness families.

- ^ Giordano, Joseph; Levine, Irving Yard. (Winter 1977). "Carter'due south Family unit Policy: The Pluralist'due south Challenge". Journal of Electric current Social Issues. xiv (1): fifty. ISSN 0041-7211. Reproduced in White Business firm Conference on Families, 1978: Joint Hearings Earlier the Subcommittee on Child and Homo Development of the Committee on Man Resources, Us Senate... Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1978. p. 490.

- ^ National Review, April four, 1994, p. 24.

- ^ Lofquist, Daphne; Terry Lugaila; Martin O'Connell; Sarah Feliz. "Households and Families: 2010" (PDF). US Demography Bureau, American Customs Survey Briefs. Retrieved 15 Apr 2013.

- ^ Camarota, y Steven A. "Births to Unmarried Mothers past Nativity and Education". Center for Clearing Studies . Retrieved eight July 2020.

- ^ "Black Marriage in America". Blackdemographics.com/. Akiim DeShay. Retrieved viii July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Billingsley, Andrew (1992). Climbing Jacob's Ladder . New York, New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 32. ISBN9780671677084.

- ^ a b Paul C. Glick, ed. by Harriette Pipes McAdoo (1997). Black families (3rd ed.). M Oaks, Calif. [u.a.]: Sage. p. 119. ISBN0803955723.

- ^ a b c Paul C. Glick, ed. by Harriette Pipes McAdoo (1997). Black families (tertiary ed.). G Oaks, Calif. [u.a.]: Sage. p. 120. ISBN0803955723.

- ^ a b Stewart, James (1990). "Back to Basics: The Significance of Du Bois's and Frazier's Contributions for Gimmicky Research on Black Families". In Cheatham,Harold and James Stewart (ed.). Black Families Interdisciplinary Perspectives. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. p. ten.

- ^ Louis, Jacobson. "CNN's Don Lemon says more than 72 percent of African-American births are out of wedlock". Politifact . Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ Paul C. Glick, ed. by Harriette Pipes McAdoo (1997). Black families (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, Calif. [u.a.]: Sage. pp. 119–120. ISBN0803955723.

- ^ Giddings, Andrew Billingsley ; foreword by Paula (1992). Climbing Jacob's ladder : the enduring legacy of African-American families (Pbk. ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 42. ISBN067167708X.

- ^ a b Giddings, Andrew Billingsley ; foreword past Paula (1992). Climbing Jacob's ladder : the indelible legacy of African-American families (Pbk. ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 44. ISBN067167708X.

- ^ Paul C. Glick, ed. past Harriette Pipes McAdoo (1997). Black families (tertiary ed.). Thousand Oaks, Calif. [u.a.]: Sage. p. 124. ISBN0803955723.

- ^ Paul C. Glick, ed. past Harriette Pipes McAdoo (1997). Black families (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, Calif. [u.a.]: Sage. p. 121. ISBN0803955723.

- ^ U.Southward. Bureau of the Census "Table 60. Married Couples past Race and Hispanic Origin of Spouses" Archived 2015-01-01 at the Wayback Machine, December 15, 2010 (Excel tabular array Archived 2012-10-13 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ U.S. Bureau of the Census "Statistical Abstract of the Usa, 1982-83" [ permanent dead link ] , 1983. Department 1: Population, file 1982-02.pdf, 170 pp.

- ^ Fryer, Jr., Roland Grand. (Jump 2007). "Guess Who'south Been Coming to Dinner? Trends in Interracial Marriage over the 20th Century". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 21 (2): 71–90. doi:ten.1257/jep.21.2.71. S2CID 12895779.

- ^ Stewart, James (1990). "Back to Nuts: The Significance of Du Bois's and Frazier'due south Contributions for Gimmicky Inquiry on Black Families". In Cheatham,Harold and James Stewart (ed.). Black Families Interdisciplinary Perspectives. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. p. 12.

- ^ Stewart, James (1990). "Back to Basics: The Significance of Du Bois's and Frazier's Contributions for Contemporary Research on Black Families". In Cheatham,Harold and James Stewart (ed.). Black Families Interdisciplinary Perspectives. New Brunswick, New Bailiwick of jersey: Transaction Publishers. p. 20.

- ^ Thomas, P. A.; Krampe, E. M.; Newton, R. R. (nineteen March 2007). "Father Presence, Family unit Structure, and Feelings of Closeness to the Father Among Adult African American Children". Journal of Blackness Studies. 38 (four): 529–546. doi:10.1177/0021934705286101. S2CID 143241093.

- ^ a b c Thomas, P. A.; Krampe, E. Thousand.; Newton, R. R. (19 March 2007). "Father Presence, Family Structure, and Feelings of Closeness to the Father Among Developed African American Children". Journal of Black Studies. 38 (iv): 536. doi:ten.1177/0021934705286101. S2CID 143241093.

- ^ Thomas, P. A.; Krampe, E. M.; Newton, R. R. (19 March 2007). "Male parent Presence, Family unit Construction, and Feelings of Closeness to the Father Amid Developed African American Children". Journal of Black Studies. 38 (iv): 531. doi:10.1177/0021934705286101. S2CID 143241093.

- ^ Thomas, P. A.; Krampe, E. Grand.; Newton, R. R. (19 March 2007). "Begetter'south Presence, Family Construction, and Feelings of Closeness to the Father Among Adult African American Children". Journal of Black Studies. 38 (iv): 541. doi:10.1177/0021934705286101. S2CID 143241093.

- ^ Thomas, P. A.; Krampe, Eastward. M.; Newton, R. R. (19 March 2007). "Father Presence, Family Structure, and Feelings of Closeness to the Father Among Developed African American Children". Journal of Black Studies. 38 (4): 542. doi:x.1177/0021934705286101. S2CID 143241093.

- ^ Thomas, P. A.; Krampe, Eastward. M.; Newton, R. R. (xix March 2007). "Father Presence, Family Structure, and Feelings of Closeness to the Male parent Amid Adult African American Children". Journal of Blackness Studies. 38 (4): 544. doi:x.1177/0021934705286101. S2CID 143241093.

- ^ John McAdoo, ed. by Harriette Pipes McAdoo (1997). Black families (3rd ed.). K Oaks, Calif. [u.a.]: Sage. pp. 184–186. ISBN0803955723.

- ^ Allen, Quaylan (2016-08-08). "'Tell your own story': manhood, masculinity and racial socialization amid blackness fathers and their sons". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 39 (10): 1831–1848. doi:ten.1080/01419870.2015.1110608. ISSN 0141-9870. S2CID 147515010.

- ^ Wilson, Melvin (1995). African American family life its structural and ecological aspects. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. pp. 5–22. ISBN0787999164.

- ^ a b editor, Melvin N. Wilson (1995). African American family life its structural and ecological aspects. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. p. 9. ISBN0787999164.

- ^ a b c editor, Melvin Due north. Wilson (1995). African American family life its structural and ecological aspects. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. p. 10. ISBN0787999164.

- ^ editor, Melvin N. Wilson (1995). African American family life its structural and ecological aspects. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. p. vii. ISBN0787999164.

- ^ a b edited by Norma J. Burgess; Eurnestine Brown (2000). African American women : an ecological perspective. New York [u.a.]: Falmer Press. p. 59. ISBN0815315910.

- ^ editor, Melvin N. Wilson (1995). African American family life its structural and ecological aspects. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. pp. 6–7. ISBN0787999164.

- ^ edited by Norma J. Burgess; Eurnestine Brown (2000). African American women : an ecological perspective. New York [u.a.]: Falmer Press. pp. 58–59. ISBN0815315910.

- ^ Margaret Spencer, edited by Harold E. Cheatham; Stewart, James B. (1990). Black families : interdisciplinary perspectives (2nd ed.). New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers. pp. 111–112. ISBN0887388124.

- ^ Margaret Spencer, edited by Harold E. Cheatham; Stewart, James B. (1990). Blackness families : interdisciplinary perspectives (2d ed.). New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers. p. 112. ISBN0887388124.

- ^ Margaret Spencer, edited by Harold East. Cheatham; Stewart, James B. (1990). Black families : interdisciplinary perspectives (2d ed.). New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers. pp. 124–125. ISBN0887388124.

- ^ a b Billingsley, Andrew (1992). Climbing Jacob's Ladder . New York, New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 58. ISBN9780671677084.

- ^ a b Giddings, Andrew Billingsley ; foreword by Paula (1992). Climbing Jacob'southward ladder : the enduring legacy of African-American families (Pbk. ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 60–61. ISBN067167708X.

- ^ a b c d e Jones, Deborah J.; Zalot, Alecia A.; Foster, Sarah E.; Sterrett, Emma; Chester, Charlene (22 December 2006). "A Review of Childrearing in African American Single Mother Families: The Relevance of a Coparenting Framework". Journal of Child and Family unit Studies. sixteen (v): 671–683. doi:10.1007/s10826-006-9115-0. S2CID 12970902.

- ^ Gordy, Cynthia. "Welfare, Fathers and Those Persistent Myths". The Root . Retrieved 2019-04-29 .

- ^ a b c McDaniel, Antonio (1990). "The Ability of Culture: A Review of the Idea of Africa's Influence on Family unit Construction in Antebellum America". Journal of Family History. fifteen (ii): 225–238. doi:x.1177/036319909001500113. S2CID 143705470.

- ^ Williams, Walter E. (June viii, 2005). "Victimhood: Rhetoric or reality?". Jewish World Review. Creators Syndicate. Archived from the original on November eleven, 2005. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ^ a b Sowell, Thomas (Baronial 16, 2004). "A painful anniversary". Creators Syndicate. Archived from the original on August xviii, 2004. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ^ MacLean, Nancy. The American Women's Movement, 1945–2000: A Brief History with Documents (2008)

- ^ a b c d east f k h i j chiliad fifty m northward o Dixon, P (2009). "Wedlock among African Americans: What does the research reveal?". Journal of African American Studies. xiii (i): 29–46. doi:ten.1007/s12111-008-9062-v. S2CID 143539013.

- ^ a b Ruggles, Steven (1997). "The rise of divorce and separation in the United States, 1880–1990". Demography. 34 (4): 455–466. doi:10.2307/3038300. JSTOR 3038300. PMC3065932. PMID 9545625.

- ^ a b c d e Akerlof, Thou. A.; Yellen, J. Fifty.; Katz, M. L. (1996). "An analysis of out-of-union childbearing in the United States". The Quarterly Journal of Economic science. 111 (2): 277–317. doi:10.2307/2946680. JSTOR 2946680.

- ^ Prison and Jail Inmates at Midyear 2006 Archived 2013-03-03 at the Wayback Car (NCJ 217675). U.South. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Male incarceration by race. The percentages are for adult males, and are from folio 1 of the PDF file Archived 2011-10-27 at the Wayback Automobile.

- ^ a b Dyer, W.One thousand (2005). "Prison Fathers, and Identity: A Theory of How Incarceration Affects Men'south Paternal Identity". Fathering: A Journal of Theory, Enquiry, and Practice About Men as Fathers. three (3): 201–219. doi:x.3149/fth.0303.201. S2CID 12297600.

- ^ a b c Brown, Tony; Patterson, Evelyn (28 June 2016). "Wounds From Incarceration that Never Heal". The New Republic. The New Republic. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ^ Toll, Lee. "Racial discrimination continues to play a role in hiring decisions". Economic Policy Institute. EPI. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ^ Wildeman, Christopher (September 2010). "Paternal Incarceration and Children'south Physically Aggressive Behaviors: Prove from the Delicate Families and Child Wellbeing Study". Social Forces. 89 (1): 285–309. doi:10.1353/sof.2010.0055. S2CID 45247503.

- ^ Rose Thousand. Rivers, ed. past Harriette Pipes McAdoo; John Scanzoni (1997). Black families (3rd ed.). Grand Oaks, Calif. [u.a.]: Sage. p. 334. ISBN0803955723.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Heiss, Jerold (August 1996). "Effects of African American Family unit Structure on School Attitudes and Performance". Social Problems. 43 (3): 246–267. doi:10.2307/3096977. JSTOR 3096977.

- ^ a b Staples, [compiled by] Robert (1998). The blackness Family : essays and studies (6th ed.). Belmont, Calif.: Wadsworth Pub. Co. pp. 343–349. ISBN9780534552961.

- ^ a b Staples, [compiled by] Robert (1998). The black family : essays and studies (6th ed.). Belmont, Calif.: Wadsworth Pub. Co. pp. 37–58. ISBN9780534552961.

- ^ a b c Claude, J. (1986). Poverty patterns for black men and women. The Black Scholar, 17(5), 20–23.

- ^ a b U.South. Census Bureau. Current Population Survey. People in Families by Family unit Structure, Age, and Sex, Iterated past Income-to-Poverty Ratio and Race: 2007: Below 100% of Poverty – All Races Archived 2008-09-thirty at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b U.South. Census Bureau. Current Population Survey. People in Families by Family unit Construction, Age, and Sexual practice, Iterated by Income-to-Poverty Ratio and Race: 2007: Below 100% of Poverty – White Solitary Archived 2009-04-13 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b "Poverty iii-Part 100_06". Pubdb3.census.gov. 2008-08-26. Archived from the original on 2011-06-12. Retrieved 2010-09-16 .

- ^ a b "Poverty 2-Part 100_09". Pubdb3.census.gov. 2008-08-26. Archived from the original on 2010-01-08. Retrieved 2010-09-16 .

- ^ a b c d Cain, D. S., & Combs-Orme, T. (2005). Family construction effects on parenting stress and practices in the African American family. J. Soc. & Soc. Welfare, 32, 19.

- ^ Zimmerman, G. A.; Salem, D. A.; Maton, K. I. (1995). "Family Structure and Psychosocial Correlates among Urban African‐American Boyish Males". Child Development. 66 (vi): 1598–1613. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00954.x. PMID 8556888.

Regardless of the causality, researchers have found a consistent relationship between the current African American family structure and poverty, education, and pregnancy.

- ^ a b c d Dittus, P. J.; Jaccard, J.; Gordon, 5. V. (1997). "The touch on of African American fathers on boyish sexual behavior". Journal of Youth and Boyhood. 26 (4): 445–465. doi:10.1023/a:1024533422103. S2CID 142626784.

- ^ Scott, Joseph (1993). "African American Daughter-Female parent Relations and Teenage Pregnancy: 2 Faces of Premarital Teenage Pregnancy". Western Journal of Black Studies. 17 (ii): 73–81. PMID 12346138.

- ^ Yacob, Anaiah (2015-02-06). "The State of Blackness Family Structure 2015: A Curse of Dysfunctional Family". WhoAreIsraelites.Org . Retrieved 2016-xi-06 .

- ^ Moore, Mignon; P. Lindsay Chase-Lansdale (2001). "Sexual Intercourse and Pregnancy among African American Girls in High-Poverty Neighborhoods: The Function of Family and Perceived Customs Environs". Journal of Marriage and Family. 63 (4): 1146–1157. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.01146.ten.

- ^ a b c d eastward f g h Magnet, Myron (2008). "The Great African-American Enkindling". City Journal. 18 (3).

- ^ a b c d east f g h i j k l k north Hattery, Angela J.; Smith, Earl (2007). African American families. M Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications. ISBN9781412924665.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/African-American_family_structure

0 Response to "Mother and Child Family Residential Services in Utah"

Yorum Gönder